Last week we shared some awesome news: David Lieb, the creator of Bump (part of the summer 2009 batch!) and Google Photos, has joined YC as a Group Partner.

I sat down with David to hear more about his story so far, and I've shared that conversation below. He'll tell us why he built Bump, why he chose to pivot it even after it saw many millions of downloads, and how that choice led to the creation of Google Photos. He'll talk about the doctor appointment that changed his path in life, what it's like seeing YC from the other side, and what he wishes he knew when he was just getting started.

What’s the Dave Lieb origin story? Where does your story begin?

Oh, gosh. How far back do you want to go?

I grew up in Texas. I was always into math and science, probably because of my parents generally being math and science-y people. When I finally escaped Texas and went to college at Princeton, I saw an entire world out there that I had no idea existed. Then I came out here for grad school at Stanford — I didn’t want to get a job after college, so grad school sounded pretty good.

While there I worked in what would become Sebastian Thrun’s AI research lab — he was one of the co-founders of Google X, and their self-driving car project that became Waymo. I was really lucky to get to work with him for a bit.

I decided to bail on the PhD and finished my Master’s and I went to work at Texas Instruments back home in Texas, until I got the bug to be more than an engineer. I went to business school, and that’s where I left the traditional path of an engineer and went into the startup world with Bump.

Tell me about that. Where’d Bump come from?

It was kind of an accident, I guess is how I’d describe it. It was a side project.

As an engineer now going to business school, a lot of the early classes were things I’d already learned. So I had a bit of free time on my hands.

Coincidentally, I met a kid who was in grad school who over the summer had made one of the first iPhone apps that would find open WiFi networks near you. He told me the story of how he made this app in a few weeks, sold it for four bucks a pop, and ended up making something like $100,000 that summer.

I thought “Wow — that’s interesting… I should be poking around these new iPhones.”

That got us thinking about different iPhone apps and problems to solve. The [problem] that was really acute to me as a new business school student was meeting all of these new classmates and just getting all of their numbers into my phone.

It occurred to me that we could build an app to make this really easy, yet nobody had done it yet! It was a total side project, with no real aspirations beyond trying to make something people would use and maybe make a little money like that kid did over the summer. Then we launched on the App Store and it just totally exceeded our expectations.

How’d you come to join YC back in Summer of 2009?

Largely by accident. We heard about YC by reading TechCrunch. The reason we did YC sounds crazy in hindsight, but…

In business school you have to go get an internship between your two years of school. All of our classmates were interviewing for jobs at investment banks, etc, and that just sounded terrible to us. We just wanted to build products and write code.

So we did it kind of as an excuse to… not get a business school internship. Honestly, that’s one of the biggest reasons we decided to do it. But then we came out, we did YC, and our minds were blown. Our world was totally upended and we never went back.

In 2013, Bump was acquired by Google… How’d that go down, and how did you decide to sell?

It was a long process.

The high level arc of the story is that while Bump got very popular — I think we were installed on like, 20-40% of all phones in the world at the time — we never really had a business model that was going to work. Our long term frequency of use and retention was just not good enough that we could build even an advertising-based model on top of it. It became clear after several years that there wasn’t much to be done with the Bump app itself.

At the same time, we realized that our users who were really loving it and using it actively were using it to share photos of their friends and family with each other.

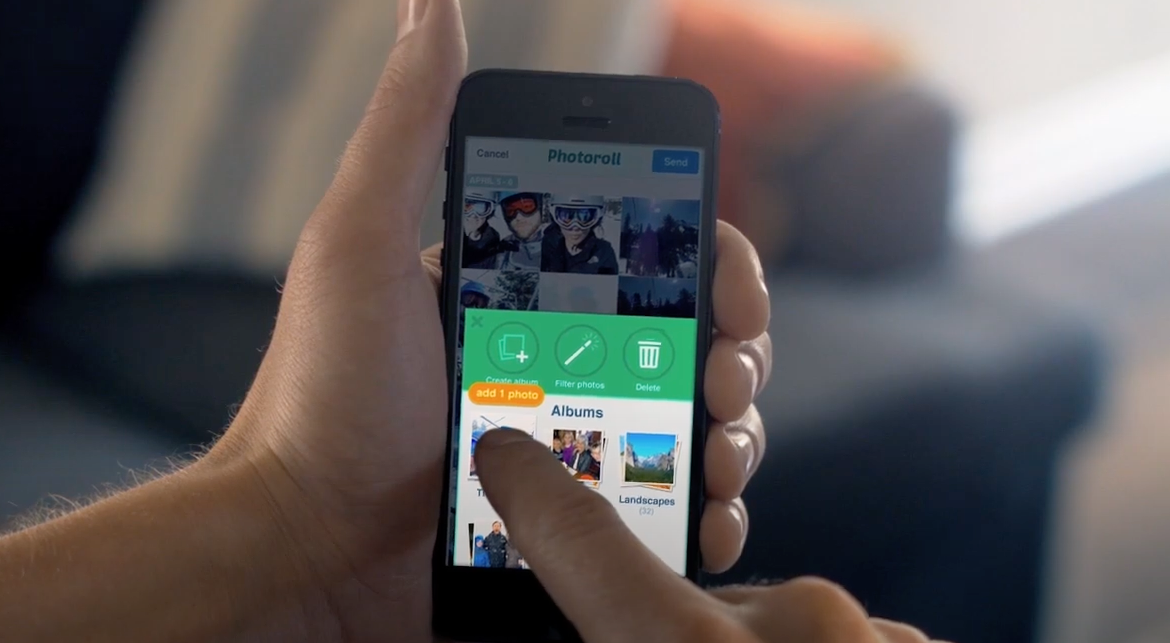

That got us on a new journey, exploring the photo sharing and photo management space. We built a couple other products that were separate from Bump to explore that, and the last one we built was basically the poor man’s version of Google Photos. All of the ideas of Google Photos, with none of the hardcore tech.

And this is still long before anything like Google Photos exists.

Yeah! I mean, the state of the art for photos on phones at the time was there was this thing called Camera Roll on your phone and that was it. No cloud backup, no search, nothing. It was just a view of your disk, basically.

So we kind of saw this future before a lot of other people saw it; we realized that people are just going to keep taking pictures, and will want to organize them, and want to share them. Yet nobody had really built the right solution to that. So let’s go build that!

That ultimately was the thing that got us acquired. We chose to sell to Google so that we could build for both Android and iPhone.

How big was the Bump team at the time?

I think at the time of the acquisition it was about 25 people. At its peak it was about 30.

So you’re going from still being a relatively small startup to being a part of Google, which even at the time was absolutely huge. What was that like?

It was a bumpy journey, to be punny.

But at the beginning, it felt really good. At the time it felt more like our 20-person team was acquiring 100 people and technology from Google, as opposed to the other way around.

[Before the acquisition] we knew exactly what we wanted to build, we just didn’t have the tech to do it. Then we showed up at Google and I remember saying “Oh, it’d be really great if we had face recognition, to automatically group all of the photos of you, your wife, your friends, whoever.”

And the response would be like “Oh — talk to Joe. He manages the 400-person engineering research team that focuses exclusively on that. Go see what he’s got.”

That just happened over, and over, and over again, on basically every core piece of technology that we knew was important to make [this Photos app] a great product.

So you’re at Google, you build what becomes Google Photos — an absolute monster success of a product, even today. You’re there for about a decade… why leave?

For a long time people were encouraging me to leave. They’d say “When are you going to do a new startup?”… and my answer was always “Well, I’ve got more I want to get done here.”

And that was an honest answer! There was more stuff I wanted to build, and whenever I did leave I wanted Google Photos to be in a position where it would be a great product for a long, long time without me. So I was hesitant to leave.

Then I got cancer.

Randomly on a Thursday I found out I had leukemia, and that I would need to be out of work for basically an entire year doing chemo to save my life. I did that and I was fortunate enough to beat it.

When I came back, and was healthy… I guess I realized two very high level things.

One was that the team, and the product, was in that spot where it would do just fine without me.

And two, having gone through that experience of almost dying and then.. not dying? It was like getting a bonus period of my life. I’m thinking, “I get some extra innings that not everyone gets. How do I want to use them?”

The answer was very much that I wanted to be back working with people in the zero-to-one phase, as opposed to managing a very large and bureaucratic organization.

I’m so glad your treatment was successful like that. What was it like when you learned the treatment would work?

It’s kind of weird: I went into the ER and I had no idea what was wrong, other than something was very wrong with me.

The way these ERs work, I’ve come to learn, is that they operate on a very strict triage system. The only thing they’re focused on for the first two minutes of you being there is: could something kill this person in the next two minutes? If so, figure that out.

Then they move on to: ok, what could kill this person in the next 30 minutes? Let’s exhaust those. Ok, what about the next two hours?

So it wasn’t for a good 24 hours that they even got far enough down this list to think: oh, maybe it’s leukemia. That was the scariest day, to be honest; I just had no information. I knew it was really serious, and I thought it might be my last day on earth. Thankfully it wasn’t.

I woke up the next day and they did a diagnostic test on my bone marrow, and the doctor came in and… I’m sure they do this all the time, but in a single sentence (so there was no time for me to get scared) he said, “we know what it is: it’s leukemia, but the good news is this type is very treatable.” He said, “Here’s the stats. It’s going to be a rough year, but you’re going to be fine.”

It allowed me to be like: well, this is a bummer, but we’ve got a year of work to do? Let’s go.

That’s incredible — the impact and weight that one statement had. Let’s flash forward a bit. It’s 2022, you’ve got leukemia beat; what now?

I went back to Google for a bit and I had that realization that I wanted to be working with startup founders again. Then the question became like… how do I do that? Should I start another company? Become a professional angel investor? Be a VC?

I had a bunch of conversations and I came to realize that the part of the job I love the most is being shoulder-to-shoulder with founders when they’re trying to make something new in the world.

It’s rare to be able to do that and not have to spend a bunch of time on other stuff, but that’s exactly what the job at YC is. We’re not typical venture investors where we’re going out and having to chase deals, and win deals, and schmooze… we have the privilege of having the best founders in the world apply on our website. We get to pick the great teams we work with.

Going to YC just felt obvious. It was the only thing I seriously considered.

Has YC changed much since you went through as a founder?

Heck yeah.

When we did YC in Summer of 2009, the entirety of the experience was as follows: you go to the Mountain View office on Tuesday nights, PG serves you chili, there’s a speaker for an hour, and then you go home.

Today we have group office hours, we have scheduled time with every company every week, we have this enormous encyclopedia of startup knowledge in the internal user manual. We have databases that help you understand who the good investors are, and who the good service providers are. We have the massive event that is Demo Day, where companies are raising millions and millions and millions of dollars. And we’ve done all that while also increasing the ratio of YC partners to founders.

It’s been super cool to see how far YC has come in that time since I went through it. It’s night and day.

Any surprises so far in seeing it from the other side, from the perspective of a Partner?

The biggest one is the way that YC operates very similarly to the startups we advise.

We’re very focused on software; it’s the core of how YC operates. We move quickly — there’s no big company syndrome or politics here. If we see a problem or an opportunity, we figure out the quickest way to solve it that day and then we iterate.

You kind of suspect that’s the way YC operates, and you hope it’s the way it operates, and then you get in and realize that’s the way it is. It’s just super reassuring — all the things that we tell startups? We’re actually doing those things ourselves. We’re consuming our own advice.

Last question! If you could go back to the early days of Bump and tell 2009 David anything, what would it be?

Oh man, so many things.

There’s a bunch of tactical things, and it’s all literally the stuff we tell founders today: don’t raise too much money, because you’ll just spend it; when you have a lot of money, don’t waste it on stupid things. Don’t hire too many people. Stay focused, all these tactical things.

If I had to pick a higher level thing, it would be: trust your gut on where this thing should go, and allow it to go those ways. During the journey of Bump, there was so much pressure on us because we raised a lot of money from fancy investors that it probably made it harder for us to see where this product wanted to go — and ultimately it wanted to become Google Photos!

I think we probably could’ve gotten there sooner if we’d just been more open to seeing it.

Originally published on Y Combinator : Original article